Grammar vs. Comprehensible Input: Who’s Right?

Inside: The role of grammar, and grammar vs. comprehensible input, in foreign language learning.

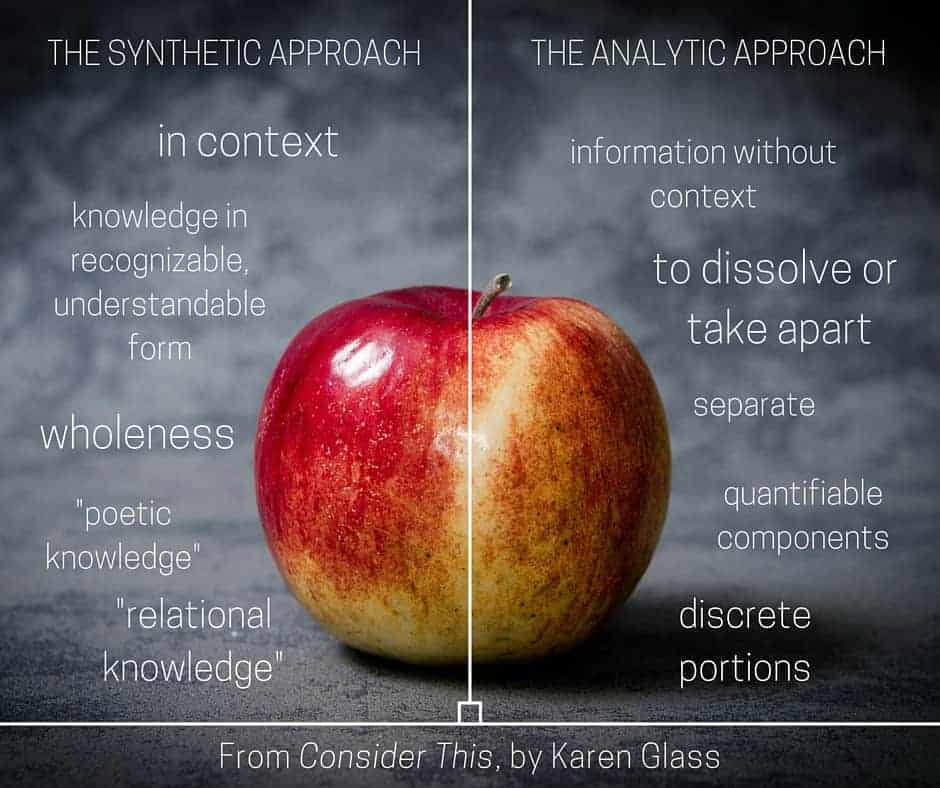

From Consider This: Charlotte Mason and the Classical Tradition by Karen Glass:

“Let us consider an apple. If we approach it synthetically, we take it as we find it– in its state of wholeness and completeness– and we eat it. Once eaten, it is digested, absorbed, and becomes a part of us. If we approach it analytically, we take it apart– not in a natural way, which is merely a smaller portion (here is half an apple!), but rather, here is the fiber, here are the vitamins, here is a bit of water, and some sugar. Suppose we ingest each bit– a spoonful of fiber, a vitamin pill, a swallow of sugar and water.

On paper, we have consumed the same thing in both cases– equal portions of nutrition– but there is a very, very large difference. Only one of those meals tasted good and created an appetite for more.

When we break apart our food-meals into discrete portions of unrecognizable substances with no wholeness or discernible relation to each other, we have no interest in consuming more of the same unappetizing matter. The same holds true for our knowledge-meals. Given knowledge in recognizable, understandable form, we consume it gladly and it tastes good. Given mere information without context, we choke on the consumption of it and never think of it again if possible.” (Consider This, 37)

Confession: I’m not here to resolve the grammar question. The word grammar— how much? when? how?– often evokes strong reactions among language teachers. I began teaching Spanish the conventional way: grammar as the building blocks to learning Spanish; only recently did I Threw Out My Textbook in search of a better way. Though I can’t tell you everything about grammar vs. comprehensible input, I want to share what I’m thinking.

THE WHY OF WHAT WE DO

As I’ve lurked on language forums and read teacher-authors, I’ve wanted to know what to do. I have wanted to know how Martina Bex begins with comprehensible input and does pop-up grammar: what is her method? I want to do it too! Glass– writing about classical education– warns,

“When we are more concerned with what the classical educators were doing than why they were doing it, we are unlikely to achieve what they achieved.”

So I am looking for the why. In reading blogs, Consider This, and reading Charlotte Mason herself, the why has became clearer: all of them were advocating a first-whole, then-parts approach.

Glass spends a large portion of the book contrasting a synthetic approach vs. an analytical one. (Last post I cited this video from Musicuentos, which also uses the term synthetic- but very differently. I don’t know why there is a difference, but just a heads up.)

“The word analysis also comes to us from Greek roots meaning “to dissolve or take apart.” If you are alive, and you attended any kind of institutional school, it is almost certain that you were taught to think exclusively in the analytical mode. In fact, upon hearing that the opposite of synthetic thinking is analytical thinking, the first response of those of so educated is likely to be, “what is wrong with analytical thinking?- we ought to analyze things!

Perhaps we ought, but not first. Analysis should not be out primary approach to knowledge or our primary mode of thinking, especially in the in the earliest years of education. We should not begin taking apart the things that we learn until we have put them together first, and so solidly unified out understanding of the world that we will lose sight of the relationships between things when we do begin to analyze. This synthetic approach to learning has been called “poetic knowledge”…”

I should have added this to last post: in beginning with grammar, we are asking students to analyze that which they don’t know or love. We ask them to study the colors of a painting they haven’t seen; to practice the notes of a song they haven’t heard. (Idea credit: Joshua Cabral)

If all this philosophizing is getting long, let me give an example.

GRAMMAR VS. COMPREHENSIBLE INPUT

I would agree with Sara Elizabeth Cotrell at Musicuentos that we cannot replicate L1 acquisition with our limited classroom time. Therefore, we must pay attention to patterns when deciding on which comprehensible input to use. When appropriate–after plenty of input– we can stop and consider those patterns explicitly. Let’s use direct object pronouns in Spanish as an example.

You see, back in the day I would have approached them analytically, first– something like this:

- Define what a direct object pronoun is (in English), and show some examples.

- Show the direct object pronouns (me, te, lo, las, etc.) and define each one.

- Show examples in sentences: Cassie tiene un libro. Cassie lo tiene.

- Exercises, games, and practice in using object pronouns. An exercise might be: Replace the nouns with an object pronoun:

¿Puedes ver la pelota? → ¿Puedes verla? or ¿La puedes ver?

Yo llamo a Alicia por teléfono. → La llamo por teléfono.

Though we “learned” this in Spanish 1, I can’t actually recall a student using this spontaneously in Spanish 1 (or for that matter, Spanish 2). Meaning, they weren’t actually acquiring this structure, even though we had worked so hard on it.

If we take a synthetic approach (the way Glass defines it), we might be reading The Boy Who Cried Wolf in Spanish, and come across these sentences: El joven cuida las ovejas. Las cuida por la noche. Las cuida en la lluvia. It only takes a few seconds to point out that las refers to las ovejas. Later on, when we read Piratas del Caribe, Raquel and Antonio will argue: ¡Tú me abandonaste! ¿Yo te abandoné? and we can pause to talk about me and te and where they are positioned. After. I might even make a lesson of it. We can briefly enter in the direct object pronouns into our interactive notebooks, with some sample sentences from texts we read.

The difference between the lessons is that in the first approach, my students don’t know who Alicia is, nor why she’s getting called on the telephone. That sentence exists entirely to make a grammar point. In fact, the students have never seen a comprehensible sentence with a DO pronon before, because the theory is to only show content after the particular grammar point has been taught.

In the second approach, the sentence “¡Tú me abandonaste!” is packed with emotion. We have been wondering the entire novel, in fact, who actually abandoned whom. That sentence illustrates a pattern my students need to acquire, andits message matters. Meaningful content, and patterns in context, have a far better chance of actually being assimilated. When I introduce a structure by first analyzing it I need many, many examples to explain it all. When we analyze something we already know–something meaningful– the context explains the structure, instead of the other way around..

To close with more of the apple analogy, Karen Glass goes on:

Further, we might pursue our knowledge of apples in different directions- many possibilities arise if we find the apple interesting. What would happen if we cooked the apple? Or froze it? Or mixed it with some other food? No affection for apples is generated by the analyzed (broken down) apple, and in fact- the greatest tragedy of all- we might not even recognize a real apple when we encounter one, if we have eaten only analyzed apples all of our lives. The implications of this as an educational hazard are sobering.

Young children should love and know “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” long before they learn that “diamonds in the sky” is a simile. New students to Spanish should have heard whole sentences and cared about them before they begin to take them apart. Though I’m still working on my how, I think I am closer to my why.

Like it? Pin it!