The Problem With Worksheets in Spanish Class

Inside: Re-thinking our dependence on Spanish worksheets/practice/skill-based activities in the classroom.

Is anyone else a teensy bit obsessed with Cult of Pedagogy?

Minimalist, just-right graphics. Oh-so-cool profile picture. And her content? — excellent. Last week she published another amazing post: Frickin’ Packets. It was spot-on. Stop right now, and good read it.

Honestly– read it, before you read the rest of this post. I’m not attempting a comprehensive essay on worksheets myself, because she just wrote one. Mine is a rambling response to her post.

Let’s talk about… frickin’ packets. Friggin’ worksheets. Our dependence on them runs deep. It says a lot about our thinking as educators. It shows how we believe students acquire Spanish.

Essentially, in this post, I’m discussing:

- Problems Behind Teaching Spanish with Worksheets

- What Makes a Good Worksheet in Spanish Class?

- Does This Mean Interactive Notebooks are Bad?

WHAT’S WRONG WITH BUSYSHEETS IN SPANISH CLASS

“In my experience, when people criticize worksheets, they are referring to a specific type of worksheet, what I will call a busysheet, the kind where students are either doing work that’s fairly low-level recall stuff–filling in blanks with words, choosing from multiple-choice questions, labeling things–or work that has no educational value at all…” – Cult of Pedagogy

The thinking behind “busysheets” in Spanish class is the real issue.

Essentially, we use them because we don’t trust the input. We don’t trust the magic of books, the stories, the songs. We don’t trust the curiosity of our students, the natural inclination of the mind to absorb interesting material, or the process of acquisition itself. (Read What is Comprehensible Input? if that paragraph sounded confusing.)

So we boil language down into a set of skills: vocabulary lists to memorize, formulas to practice. We think explaining language will get us to fluency faster than quality exposure to language. So make a packet of worksheets and feel we’ve “covered” the material because we’re holding the papers in our hands.

Worksheets are pretty darn handy for explaining and practicing things, but they’re problematic in getting us to fluency.

PROBLEM #1:

Apart from the well-established fact that teaching grammar outside the context of meaningful writing does nothing to help students become better writers, and in many cases makes them worse, the skills being practiced in this kind of worksheet don’t actually teach or reinforce the goals set by our academic standards. – Cult of Pedagogy

We often use worksheets because we are teaching a “skill.” In other words, we select a rule that can be isolated, explained, practiced, and tested. Verb drills fall into this category:

Yo _________ (correr) a mi casa.

If we drill and practice enough, our students can become quite skillful at conjugating verbs and passing fill-in-the-blank tests. But if we’re reaching for growth in proficiency (spontaneous communication of messages), busysheets won’t get us there.

As language teachers, we have to accept that language acquisition is more nuanced and less controllable than a set of skills. Providing our students with rich comprehensible input is sometimes scary because it doesn’t fit neatly into a busysheet, but it will lead to authentic communication.

PROBLEM #2:

Worksheets come between the student and living materials. The students knows there are questions to answer, and what happens? The worksheet becomes the center of attention; the text becomes a source to find the answers.

Worksheets (and textbooks) tend to lift language out of context. The language serves a purpose other than telling an enjoyable or compelling story. Students know this. Years of worksheets train them to look for answers instead of getting absorbed into the language itself. We teach students to dissect language before they have learned to love it.

Having students answer low-level recall questions about a passage of writing that offers no meaningful context doesn’t do a lot to make them better readers… So much of what we call “reading instruction” is far inferior to having students read real books.

One of the reasons I hated teaching with a textbook was that the reading passages and listening activities were inferior, as far as literature goes. I mean, I would never read or listen them for pleasure. Would you?

When I dropped the textbook and moved away from worksheets, we started reading good books and having more natural conversations. We had time for it. Direct contact with living materials– songs, videos, stories, games– is infinitely more absorbing than an out-of-context passage, rule, or vocabulary list.

I’m not saying I reached a level so compelling they’d choose my class over their phones everytime. But in reducing the worksheet-ish moments, meaningful messages took center stage.

Not sure what teaching looks like outside of worksheets and “practice”?– see my post on strategies for delivering comprehensible input.)

DO WORKSHEETS HAVE ANY PLACE IN SPANISH CLASS?

Ok, so does this mean that you have to feel guilty every time your students touch a piece of paper fresh from the copier? Here’s what Gonzalez says:

Technically, a worksheet is anything printed on copier paper and given to students to write on. And since you can print just about anything on a piece of paper, we really can’t say that worksheets per se are good or bad.

And:

Some worksheets are clearly nothing but busysheets, while others, like note-taking sheets or data collection tools, directly support student learning; I’ll call these powersheets. I think a lot of worksheets fall somewhere between the two.

Even after ditching the textbook, paper never disappeared from my class. In fact, I used interactive notebooks– which I’ll get to in a minute.

But I think she’s right: we need to think hard about what send to the copier and what we hand to students.

We can ask:

- Is this better than just reading a book or telling a story?

- Am I doing this because it is cute, or because it’s meaningful?

- Could this worksheet be reduced by half and still be just as effective?

- Is there any way to incorporate choice?

Only you, of course, know your needs and classes well enough to answer this each time.

WHAT CAN POWERSHEETS LOOK LIKE IN THE SPANISH CLASSROOM?

I’m not advocating 100% input with zero student response. Students will often respond to input in one way or another, and “powersheets” can streamline and support that. I don’t how comprehensively I can answer this, but here are some examples I think of as I move towards powersheets, and away from busysheets.

Good graphic organizers. Why?:

- They’re usually a form of digesting input– and so the focus stays on input.

- They often ask students to think higher on Bloom’s taxonomy: compare, contrast, etc.

- Even novice students can list isolated words in meaningful context with a Venn diagram, for example.

Freewrites. Ok, so this one might literally be a sheet of paper. (I personally love Martina Bex’s versions.) But SO GOOD. Why?:

- You find out *exactly* what language is in your students’ heads. What words have stuck, and what level of complexity they’ve reached.

- Choice. They say what they want and express themselves.

- If the proficiency levels are included at the bottom of the paper, the students write and then get immediate feedback– about how many words they can write in ___ minutes and what proficiency level they are reaching.

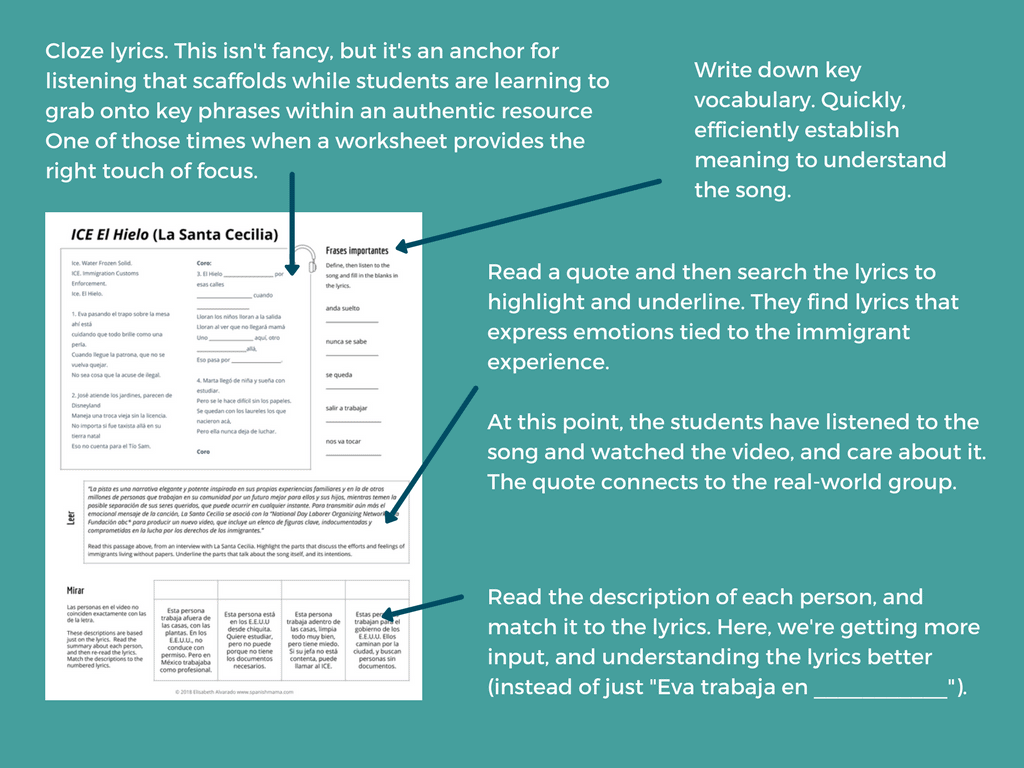

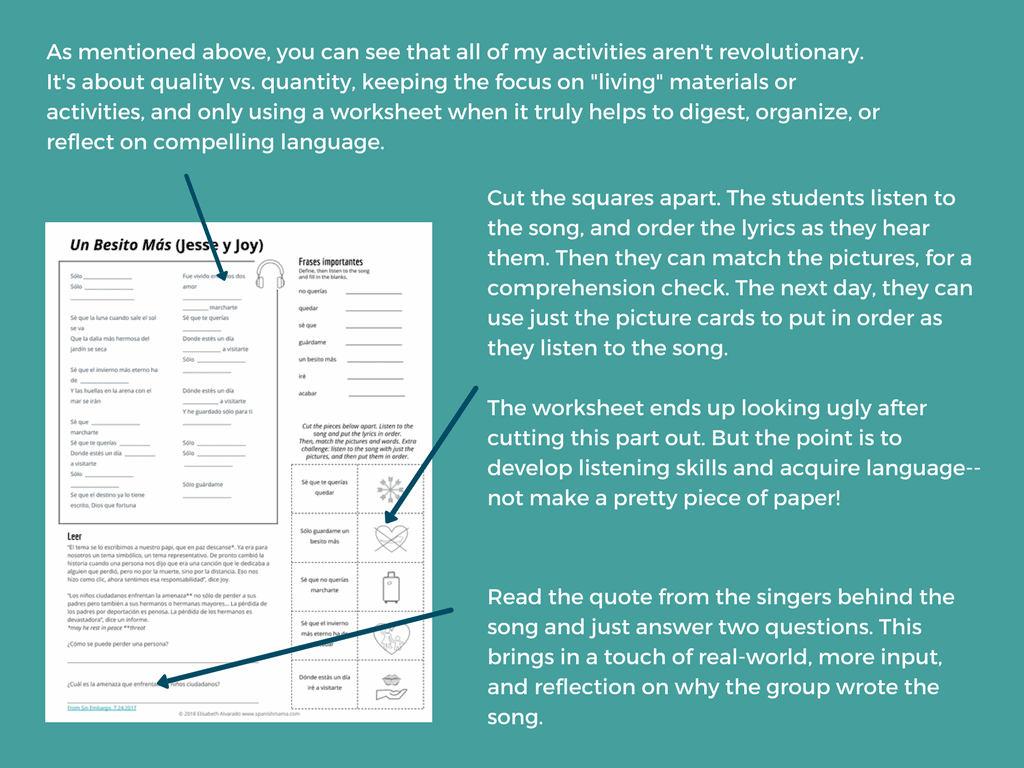

Multiple-activity sheets. Pardon the self-promotion here, but I’m going to use one of my TpT products to show how I try to judiciously use paper and create my version of a powersheet.

These sheets help us work through songs in Spanish. I try to pack in varied activities that I use over several days, as an anchor to help us understand the song and work on the skills I do think are important: listening, reading, and writing. I work really hard to fit everything on one sheet of paper, and keep the focus on the music itself.

When I make a worksheet, I think: Does this help us acquire, more than simply listening/reading/discussing the material? If so, I make it. If not, I don’t.

WHAT ABOUT INTERACTIVE NOTEBOOKS?

Many of our darling activities are not spared in Gonzalez’s post (crosswords, word searches, Google Drive activities, and others get called out). If you follow me at all and use interactive notebooks, you might thinking… umm, do I need to throw mine out???

I mean, she does say:

Interactive notebooks: These vary widely in quality, with some offering true interactivity and others just offering the same value of a worksheet, just colored, cut, and pasted into a notebook. – Cult of Pedagogy

I use and make materials for interactive notebooks. But I think she’s spot-on.

Our thinking has to change. We can throw out the textbook, and then go make a zillion worksheets. We can toss the worksheets, and call notebooks interactive because stuff lifts up and looks cute. But re-packaging won’t change our content or methods. Interactive notebooks will ONLY support acquisition if we are thinking correctly.

My interactive notebooks are not the point. Input is the point; the meat of class. Our interactive notebooks simply house and organize the input.

I also believe we should think of interactive notebooks as subordinate to language. I have a rough idea of sections in mind at the beginning of the year, but the writing, journaling, and responding that takes place depends entirely on the class and what we explore.

I’ve always told people not to bother with interactive notebooks if it doesn’t make sense to them. To me, they are a super-convenient, sensible way to store our Spanish input, organize ourselves, and digest our stories, songs, and conversations.

If you want to read more, see my page on interactive notebooks in Spanish class. I have several videos and examples to show what I do. You can take a look and decide for yourself if they’re in busysheet-land or powersheet-territory!

What do you think? Am I too harsh on Spanish worksheets? Do you love them, hate them? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

Although I absolutely agree with both you and Jennifer Gonzales that worksheets can be a waste of time for students but I think it’s ignoring the important introductory-memorization phase students go through when first encountering the language. Students need multiple and varied exposure to words and grammar ideas in order to learn them and I don’t think there is anything wrong with worksheets that deal with conjugation and vocabulary where students learn by practicing over and over again IF it is in concert with other activities. I like to use worksheets (or sections from worksheets) as exit slips or other forms of assessment where my questions is essentially, “are we able to at least to the most basic thing?” Again, this is most useful during the first few days of a unit. I have also found worksheets useful when completing unit review. It is sometimes challenging to come up with authentic resources that cover all of what you are going to assess but an artificial interaction with the language (like a worksheet) can. I usually give these to students as study guides or reminders of what we covered in the unit. I usually wont collect them and I tell the students that they should scan the sheet and only complete what they think they need help with.

I really love your detailed example of what a song “powersheet” can look like!

Really love your example powersheets for a Spanish classroom! They get at the heart of the content and ask students to do more than just recall song vocab, so students can truly interpret the messages behind the songs and build their interpretive skills. My only disagreement is that counting up how many words students can write during a free-write is not a direct indicator of proficiency. Proficiency is based on their language function, text type, impact and so much more. I use the ACTFL-produced rubrics from the ACTFL book “Implementing Integrated Performance Assessments” to assess students’ performance (which can lead to an indicator of proficiency). A true indication of proficiency would have to be done by a proficiency assessment!

Ah yes– I use free-write sheets from Martina Bex that have re-phrased ACTFL indicators at the bottom. So, the students at a glance can see both if their number of words are increasing, and check their proficiency against the indicators. Totally agree that it’s more about complexity of speech!

I would love to move towards teaching with more comprehensible input. I get excited every time I read blog posts like this. My only problem is that the rest of my department focuses heavily on grammar. How can I make this jump if they are “expected” to know conjugation tables in the next level? Any suggestions?

This is one of the reasons I include verb chart-ish stuff in my notebooks. It’s a big question, and you might find better answers by searching in the CI Liftoff FB group, or https://www.facebook.com/groups/IFLTNTPRSCITEACHING/. I focus on CI most of the year, and then do some grammar at the end. They tend to catch on quickly because it’s explaining patterns they have probably already noticed, and have the context for.

It’s exposure to patterns that facilitates acquisition of grammar. That comes from using the target language in context and authentic materials. Explaining grammar in English and before students are asking is a huge waste of time. Furthermore it kills motivation and raises the affective filter.