Why I Stopped Trying So Hard to Get My Students to Speak Spanish

Inside: Shifting our thinking on speaking in the language classroom, and creating space for confident speaking.

As a new teacher, I was determined to get my students speaking. Everybody wants to get their students speaking, right? It’s the holy grail of language class: communication, conversation.

I mean, why are we teaching Spanish, if not to produce students who can speak it? And yet… one of the biggest frustrations is students who don’t speak, don’t stay in the TL, or don’t participate.

For me, the most dramatic improvements in speaking came when I let go of “getting my students to speak up.”

WHAT? Ok, bear with me.

In those early days, I was frustrated that my students weren’t speaking in Spanish like I’d hoped. They were holding side conversations in English; silence followed when I asked questions. Even my eager students hesitated to speak. What was I doing wrong?

First, I was tempted to blame them. They had bad attitudes, or were lazy. I needed to be stricter about “Spanish only.” I needed to immerse them more, set a higher standard, you know?

Try harder! If you don’t speak, you won’t learn Spanish.

So I implemented systems. Tickets, charts, punishments. You know the drill. And still– I wasn’t getting the spontaneous communication I wanted.

Finally, I began to wonder if the reason was deeper. Maybe it was deeper than not having good enough systems, or fancy enough rewards and consequences.

And one day, I stopped trying so hard to “get them to speak.” I started focusing on making our time together compelling and meaningful, trusting that communication would follow. I had been trying to pull my little plants to make them grow faster. I stopped measuring their growth so much; I started focusing on the soil, the water, and the sun: the parts I could actually control.

(Before I dive in, I KNOW some classes are difficult and just harder than others. I know some classes aren’t staying in the TL language, and it’s a discipline issue. I know students aren’t passive plants. I’ll address this at the very end of the post, don’t worry!)

But I also believe that most students, deep down, are attracted to meaning. They want to communicate. They have things they care about, and want to feel successful in class.

So what was I doing wrong?

6 WAYS I WAS SABOTAGING SPEAKING IN CLASS

1. INAPPROPRIATE EXPECTATIONS.

As a new teacher, my expectations for output were way too high. No wonder my students shut down! I was doing many activities they couldn’t be successful with, no matter their determination.

When I became familiar with the ACTFL guidelines, I was shocked. It was also a huge breath of fresh air. Novice-low was expected to produce lists, not full spontaneous sentences with perfectly conjugated verbs? WHAT? Here’s what the ACTFL has to says about Novice speaking levels:

“Novice-level speakers can communicate short messages on highly predictable, everyday topics that affect them directly. They do so primarily through the use of isolated words and phrases that have been encountered, memorized, and recalled. Novice-level speakers may be difficult to understand even by the most sympathetic interlocutors accustomed to non-native speech.”ACTFL Speaking Standards

It wasn’t lack of rigor, then— in fact, my imagined rigor was probably producing rigor-mortis. I had to re-adjust my expectations, re-work many activities, add lots of visual supports, and really re-work how I spoke to them.

For my novices, my questions were often too open-ended, so that even when they wanted to respond, they didn’t have enough language to do so (which made them feel like they were “behind” or “bad at languages,” and increased the fear factor). When I began rely heavily of yes/no questions, either/or, and one-word answers, participation increased. I became more skilled at differentiating as I communicated, as well– adjusting individual questions to a particular students level.

2. OVER-EMPHASIS ON ACCURACY.

Back when I taught with my textbook, the backbone of my units were grammar points. Instead of providing rich, whole language, we were hyper-focused on something like ser vs. estar, or memorizing the irregular preterites. So when my students spoke, they were trying to construct rules and piece together bits of language, while worrying it would come out wrong.

This paralyzed them, obviously. When explicit grammar lessons took a backseat, I naturally switched to giving them whole language from the beginning. I didn’t present ser as a conjugation chart: I introduced it as “Mira clase, hay una chica. ¿Es alta or baja?” And bam— in the first week of Spanish they were responding in phrases, just like that: “¡Es alta!” without mentally running through a conjugation chart to land on es. When I laid off the explanations and just told them what a phrase meant, they ran with it.

The day I realized ACTFL classified consistently conjugating verbs correctly as an advanced-level skill I felt FREE. Accuracy has a place, but it’s a small place in novice-intermediate levels. An over-emphasis on accuracy, will hamper risk-taking and fluidity in speaking. This quote says it better than I can:

I would humbly submit to you that many teach grammar and syntax as prerequisite knowledge for communication. I contend that this notion is misguided, at best, and leads us down the wrong path instructionally. Grammar and syntax are important, not for the creation of communication, but rather for the avoidance of miscommunication.

– Jon De Mado, On the Role of Grammar

3. NOT CENTERING THE COURSE ON HIGH-FREQUENCY WORDS.

When I followed my textbook to a T, we learned ar, er, and ir verbs in-depth because they were “easier” than irregular verbs like “gustar” or “tener.” It was months before we got to those.

I suppose the textbook was arranged that way because the thinking goes how can you use and understand a word you couldn’t explain/dissect? (Even though my two-year-old could, just like most English speakers can use do and does quite accurately, without being able to explain why.)

But how the heck can you have a interesting conversation without gustar? Once I focused FIRST on high-frequency verbs, the change was huge. We could talk about SO MANY THINGS. We could get the gist of SO MANY authentic songs and #authres. If students know even twenty core words, so much can be said.

4. PHONY CONVERSATION TOPICS.

My students are human beings. They are actually dying to talk and communicate: it’s why I have to make rules about side conversations. They LOVE sharing their opinions and talking about themselves.

They’re just not dying to talk about inane topics. Before I centered my program on high-frequency words, we were stuck in really unnatural partner activities and conversation. Every teacher– no matter the method– can fall into the land of boring and pointless conversation.

So I began a new rule of thumb: if we wouldn’t talk about it in English, why would we talk about it in Spanish? If the game wouldn’t be fun in English, why are we playing it in Spanish? I began choosing games that were so fun, they wanted to speak Spanish— not because they were practicing, but because they were lost in the fun of the task (= game, in this instance). Mafía, Mano Nerviosa, Manzanas a Manzanas, and the Circumlocuation game are good examples of this.

I am by no means 100% successful here, but I’ve learned to take a step back if a class discussion is bombing: is it really that my students are being uncooperative, or did I just ask a dumb question? Are we dealing with bad attitudes, or would I also be crying inside if I had to talk about this for 20 minutes?

5. LACK OF FOCUS ON INPUT.

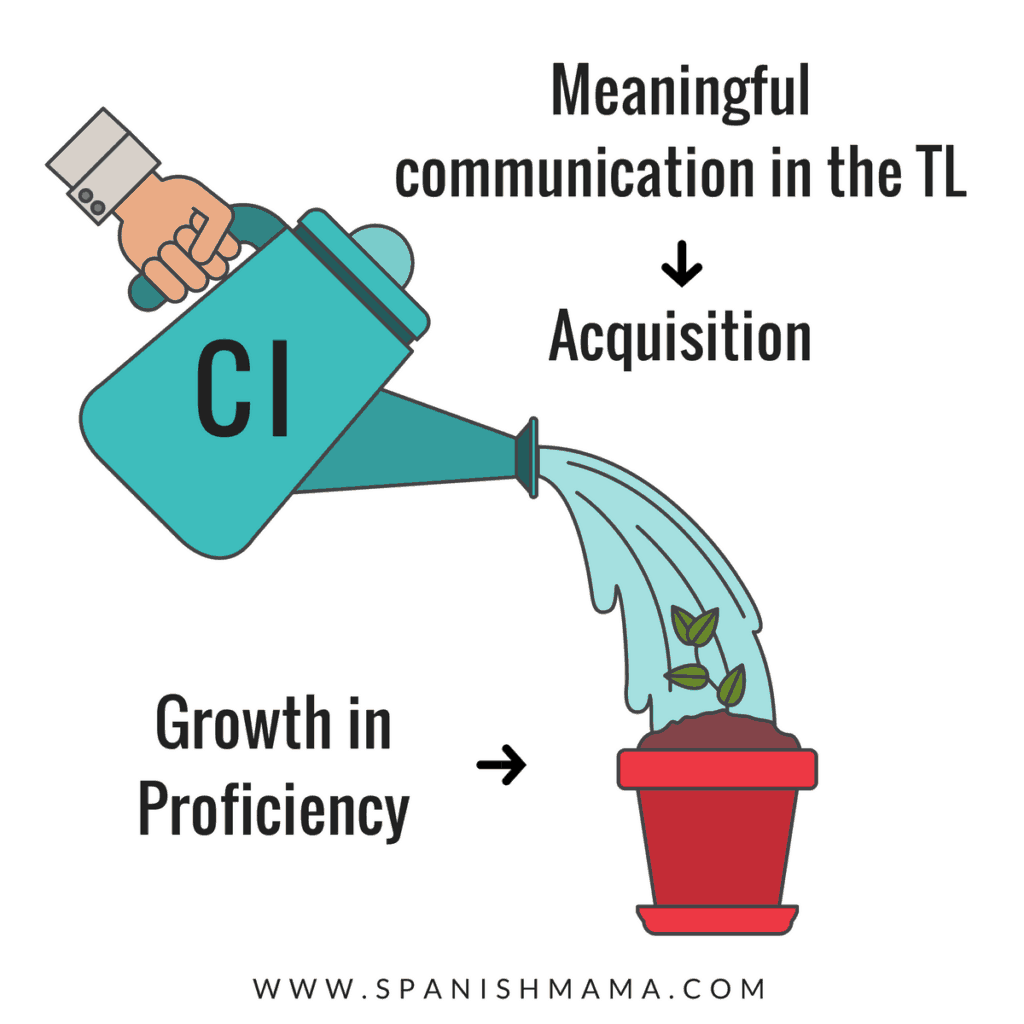

Ironically, when I had an output-focused mindset, the output was worse. When we did lots of memorized dialogues, presentational tasks, paired partner speaking, and games that “practiced” speaking, the output suffered. You can actually acquire a language on some level, without speaking. You can’t speak a language without massive input, though.

When I let go of “getting my students to speak Spanish,” I focused my energy on fantastic, compelling input. I gave them tons and tons of things to read. I told them stories and held conversations, and we watched movies and listened to songs. I zeroed in on what my students cared about.

I stopped the endless quizzes to know what they’d memorized the night before. I stopped thinking they could memorize their way into fluency. My assessment in the lower levels became more relaxed and unrehearsed (“tell me about your family”) as I began to search for what language had made its way into their minds, and could naturally flow out.

And guess what? The output blossomed. When I let go of “getting my kids to produce,” they largely spoke when they were ready.

6. CHANGING MY IMMERSION MINDSET.

When I clung to the idea of immersion, I was not understanding that all input is NOT equal. Comprehension was more important than immersion. My immersion was a lot of noise. It made my students shut down. When I allowed myself to speak English, I found that 10% of class spent in English made the 90% REALLY effective. To me, 90% of class time in Spanish that is comprehended Spanish is better than 100% of class time in Spanish that is only 70% comprehended.

(This isn’t to say that teachers who do 100% immersion are wrong— as long as they’re getting 90%-100% comprehension, we’re on the same track. I just found that allowing myself 10% in English meant a rich 90% in Spanish. It may be I haven’t developed the skills to do this.)

CONCLUSION

I don’t mean to paint my classroom as rainbows and unicorns— there was/is still a range. There were still students who didn’t gush over Spanish and decided not to take Spanish 3. And in the end, our students are not passive plants. They can choose to pay attention and participate, or not.

So in the end, I STILL found some of speaking-in-the-TL systems helpful. Why?

First: I speak Spanish. And yet, with my friends who are native English speakers but also speak Spanish, we chat in Spanish. People by nature revert to what is easiest and most comfortable, so most people need accountability.

Second, there will always be classes whose departure from the TL is a character issue. Sometimes it is a discipline issue, and sometimes an issue of laziness. I keep my systems lighthearted, like a game, and celebrate their speaking like a crazy. I gush over bravery in speaking, and celebrate them.

One year, in the spring, I told a level-2 class they would get ten minutes to watch extra, at the end of the period. If they unlawfully spoke English, I’d erase a minute. If I slipped up and said anything in English, they got an extra minute. We had so much fun with this, and it worked for that last stretch of the school year when everyone was stir crazy.

My favorite post with ideas for target-language accountability is this quick one one from Sherry, at Secondary Spanish Space, and then her longer post at World Language Café.

I would love to hear your thoughts too. Let me know in comments below!

Hola Elisabeth! I’ve been following you for a while and this post really made me think and resonated with me! I especially liked when you talk about stop focusing so much on the output and start doing it more on the input. I’ve seen in my teaching years an over-importance on the output as a measurement of learning and success – to the point to even try to force it. Lack of focus on the input, as a result, subtracts the student of the necessary input to acquire the building blocks to produce that output.

Anyway, it was a great read, thanks! And keep up with the good work.

Hi Elisabeth. I loved reading through your experience with your focus on input to create output.

Three years ago, I went to a TPRS conference, and I was floored. I had just spent my first year teaching with a traditional approach, and had seen a lot of success with some of my students, but I had also seen a real struggle for some of my students who didn’t pick language up as easily. I was transitioning to a new school that supposedly taught using TPRS.

When I got to my school, I learned that they had just chucked their TPRS curriculum because they felt the kids’ understanding of grammar was very weak. So I was back to a traditional curriculum.

I try to get as much CI into my classroom and lessons as I can, but it’s challenging. I teach Spanish I to 7th and 8th graders, and after their 7th and 8th grade year they go on to Spanish II as freshman (assuming they did ok in Spanish I).

The more I try to “get through” all of my curriculum stuff the less it seems I get through. But I feel stuck where I’m at, because my students are expected to know what it means to conjugate an -ar verb and when to use ser vs. estar.

I have looked for resources that go along with the curriculum that my school uses (realidades) but I am only one person-I don’t have time to completely re-write a curriculum for TPRS that still teaches my students everything they need to know.

I currently follow along with the curriculum and what my kids have to know and try to add in TPRS lessons, movietalks, and other CI stuff as much as possible. But I feel like I’m doing my kids a disservice, and I feel like a lousy teacher at times. What suggestions would you give me?

Elisabeth, do you have a “list” or suggestion towards those high frequency words/units?