What Everyone Needs to Know About Language Proficiency

Inside: What is language proficiency? What does it mean for my Spanish classroom?

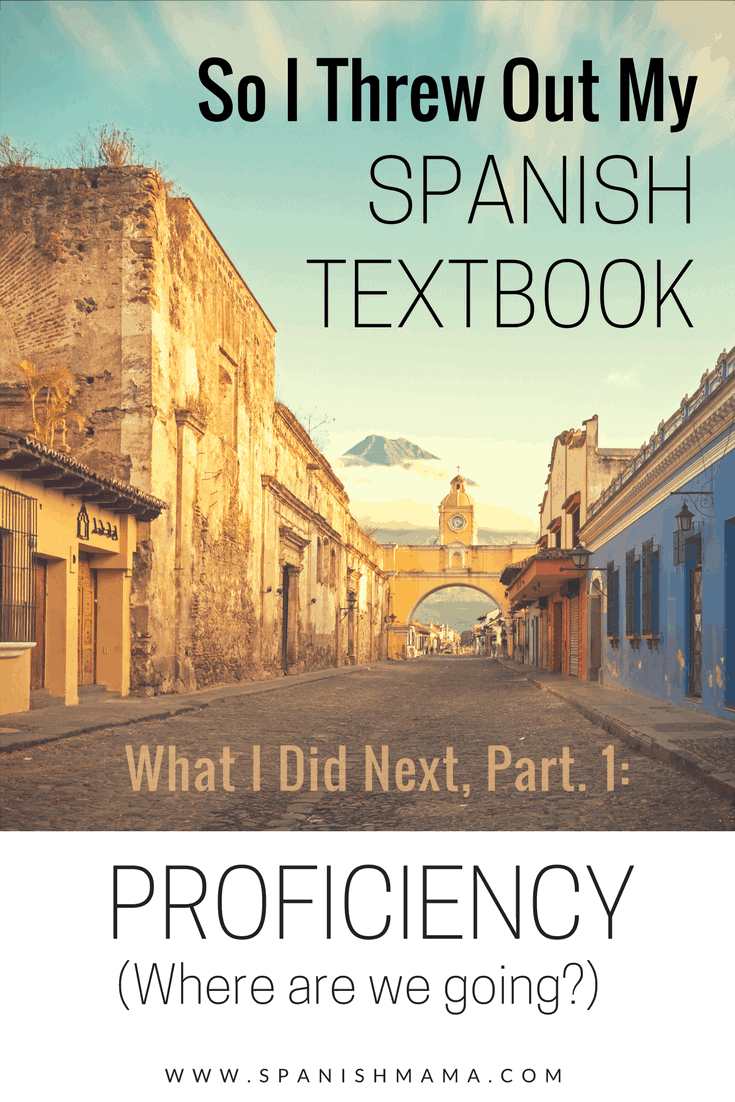

Last year I wrote a post explaining why I was throwing out my Spanish textbook. Of course, throwing it out was the easy part. But what to do next?

I’m writing this series because I remember so clearly what’s it’s like, to be on the edge of that cliff– poised to jump into textbook-free land, with a mind-boggling array of choices below. I just wanted someone to hold my hand, help me sort it all out, and put me touch with the experts. And that’s exactly what I’d like to do here.

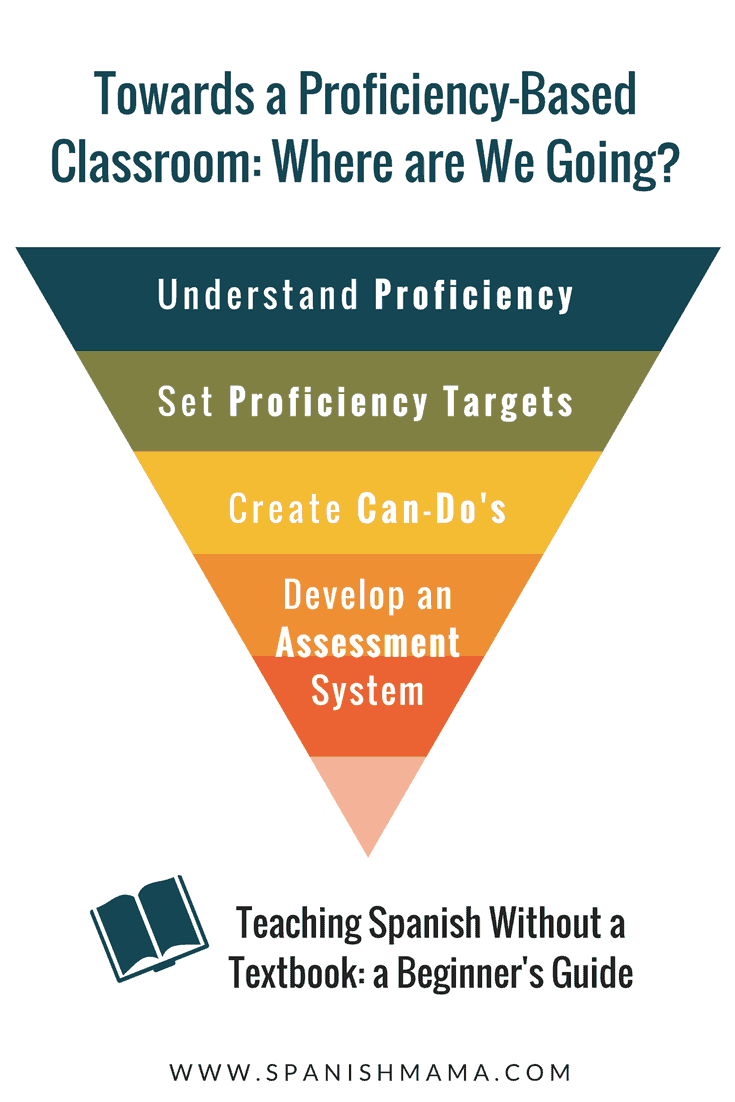

So, here’s my after-story to going textbook-free. I found I had three major tasks in developing a plan for the year: figure out our objectives, research how students acquire language, and then choose methods and develop content. Here in Part 1, I’ll share how I formed a big picture and zeroed in on targets for each class.

(When researching how to teach Spanish without a textbook, I got bogged in what to do. TPRS, IPA’s, #authres, OWL… and my head felt like exploding. If you feel like that, take a step back. All of those methods are ways of getting language into the students. We’ll talk about those in Part 2 and Part 3. The first task is figuring out where we are going.)Teaching to ProficiencyWhat is teaching to proficiency in the language classroom?

1. FIRST, WHAT IS LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY?

I had been working really hard to make our study of Spanish “stick,” but I was frustrated that my students could barely speak. I thought I was a bad teacher. With my textbook I was doing a good job of covering the chapters, actually, but I wasn’t pursuing real-life communication as our end goal. I didn’t understand proficiency, and therefore I wasn’t teaching to proficiency.

To avoid my experience, make sure you are crystal-clear on this:

At the end of the year, what should the students be able to do?

The light bulb finally when off when I thought about this way: if my students were dropped off in Santiago, Chile, what could they say? What could they write, understand, and read? That was the language inside their heads. That moment–not a big grammar final exam– could shape my teaching. This helped me to sort through what language they needed right away, and where we’d be later. Before I got caught up in methods, I needed this big picture in my head.

I began thinking about helping my students “rise in proficiency” as Joshua Cabral at World Language Classroom says. I stopped thinking in terms of testing knowledge about Spanish– 1. Yo _____ a la escuela. (ir)– for example. Learning Spanish isn’t mastering a set of skills; it’s growth in complexity of messages.

Now I am constantly watching what messages my students can understand, and what messages they can produce. Each week, their language gets a tiny bit more complex. Their proficiency levels tell me what language they need next, and how to pace our classes.

2. NEXT, SET PROFICIENCY TARGETS FOR YOUR CLASSES

Now that I understood proficiency, I began researching the ACTFL benchmarks and develop an idea of where you’d like each class to be.When I became familiar with the ACTFL standards, it made sense as I thought about how my own bilingual children were learning language.

- They had a silent period, learned some words, then went on to phrases, and started producing increasingly complex sentences.

- They understood more than they could produce.

- They generally learned the language they needed first: communicating needs, likes, simple descriptions.

While a teenager’s process in a classroom isn’t not identical to my bilingual baby’s experience, it was still a useful comparison. In a more natural progression, my Spanish 1 class would generally start by producing memorized phrases. They’d probably be speaking about themselves, about familiar topics, and concrete things happening in the present tense. And guess what? That’s what is generally described as Novice-Mid or Novice High.

I found the following sites really helpful in understanding language proficiency targets and creating a roadmap:

The OHIO Department of Education provides a great breakdown of matching proficiency targets to specific courses.

Jefferson County Schools ACTFL Guidelines has a detailed outline of aligning ACTFL targets and can-do’s to Spanish 1a, Spanish 1b, etc.

Martina Bex has a clear example of her proficiency targets aligned with specific classes. I use a very similar outline to hers.

3. THEN, FORM SOME OVERALL CAN-DO’S FOR EACH CLASS

For Spanish 1, I set goals like these:

- I can talk about and describe myself, in full sentences.

- I can introduce and describe my friends, in full sentences.

- I can order food at a restaurant.

- I can read a book written at a Novice-High level.

On a day-to-day basis, the Can-Do’s will be smaller, but it helped me to outline the big ones at the beginning of the year. Then I could base my planning around the input (stories, songs, conversations, movies, novels) I wanted to use. I don’t really to daily targets (perhaps I should), because it’s usually input over a period of time that produces a Can-Do.

A word of caution:

It’s tempting to think of the ACTFL statements and Can-Do’s as a set of skills to memorize, but avoid this. Having your students practice a monologue about themselves over and over might make it seem like they’ve achieved “I can talk about and describe myself.” But could they still do that in 2 months? It’s really important to understand comprehensible input and acquisition before starting those lesson plans!

I really on freewrites and spontaneous questions/conversations to know what my students can do, not tests that we practice for.

4. AND THEN DEVELOP A SYSTEM FOR ASSESSMENT

Teaching to proficiency meant a radical change in my grade book and how I assessed. I dropped the old categories of Quizzes, Tests, Homework, etc., and replaced them with Listening, Reading, Speaking, and Writing, with a small percentage for Work Habits. I didn’t want to know how hard my students had studied the night before; I want my assessments to tell me what language is actually in their heads. I am still working out the kinks in the system, but I have a clear idea of what my students know and need now.

Most of the time I only assess actual proficiency, with completely unannounced, random assessment like those described by Magister P. I used to give tons of vocabulary quizzes, and the results basically told me who had a great short-term memory. At one point this year, I just asked my Spanish 1 students to tell me about their families, one-by-one. From that short conversation, I could tell what structures they had actually acquired, whether they were speaking mostly in memorized phrases or original sentences, what vocabulary was at their disposal, and how accurate/detailed their speech was (in talking about a familiar topic). This probably sounds very rudimentary to a veteran proficiency-based teacher, but for me it felt like a game-changer.

(If you would like much more in-depth info. Musicuentos has a Proficiency Rubric and more detailed explanation of assessment than I wanted to get into here. And her Tacos example is not to be missed.)

Sometimes, like for the food unit, I use an IPA, which tests performance more than proficiency. In that case, my students have real-life opportunities to order food in Spanish, and we devoted a unit to it. Juice and bread might not be super high-frequency in the grand scheme of the Spanish language, but my class was really excited to use these words in real life.

Once I stopped thinking what my students could say about Spanish, and started thinking about what they could do, my classroom transformed. I’m not exaggerating when I say the grammar cloud lifted, and communication in Spanish became front and center. The magic I’d felt as a language learner came back, and finally made sense.

Like it? Pin it!

Love this article and opinions! This is the fist post I have read on your website and it’s great! You are ahead of me in the “how to teach language in a meaningful way” journey. Thanks for sharing that!

I love your words here. I am wanting to become proficient in Spanish; right now, I have the opportunity to teach students whose first language is Spanish – but they also usually know English. My vocabulary is not bad, but I don’t have the ability to string those words into sentences. I can understand a lot of the conversation, but not enough to join. I have been really pondering the bridge between understanding and producing some conversation. I would love to just jump over to a Country where I would be forced to speak the language – as a baby is in their first environment!

I agree with you totally but still find myself doing the odd vocab quiz or grammar test. Do you believe there is no point in doing these?

Thank you so much for sharing this (and your whole blog really). I had never heard of TPRS before, and am going into my first year of teaching this Fall. I’m really excited to read through your resources and start putting some of this to use. I’ve always been frustrated by how many people get through 3 or even 4 years of Spanish and can’t speak anything, this sounds like a great way to teach actual language learning instead of just the ideas and vocabulary.